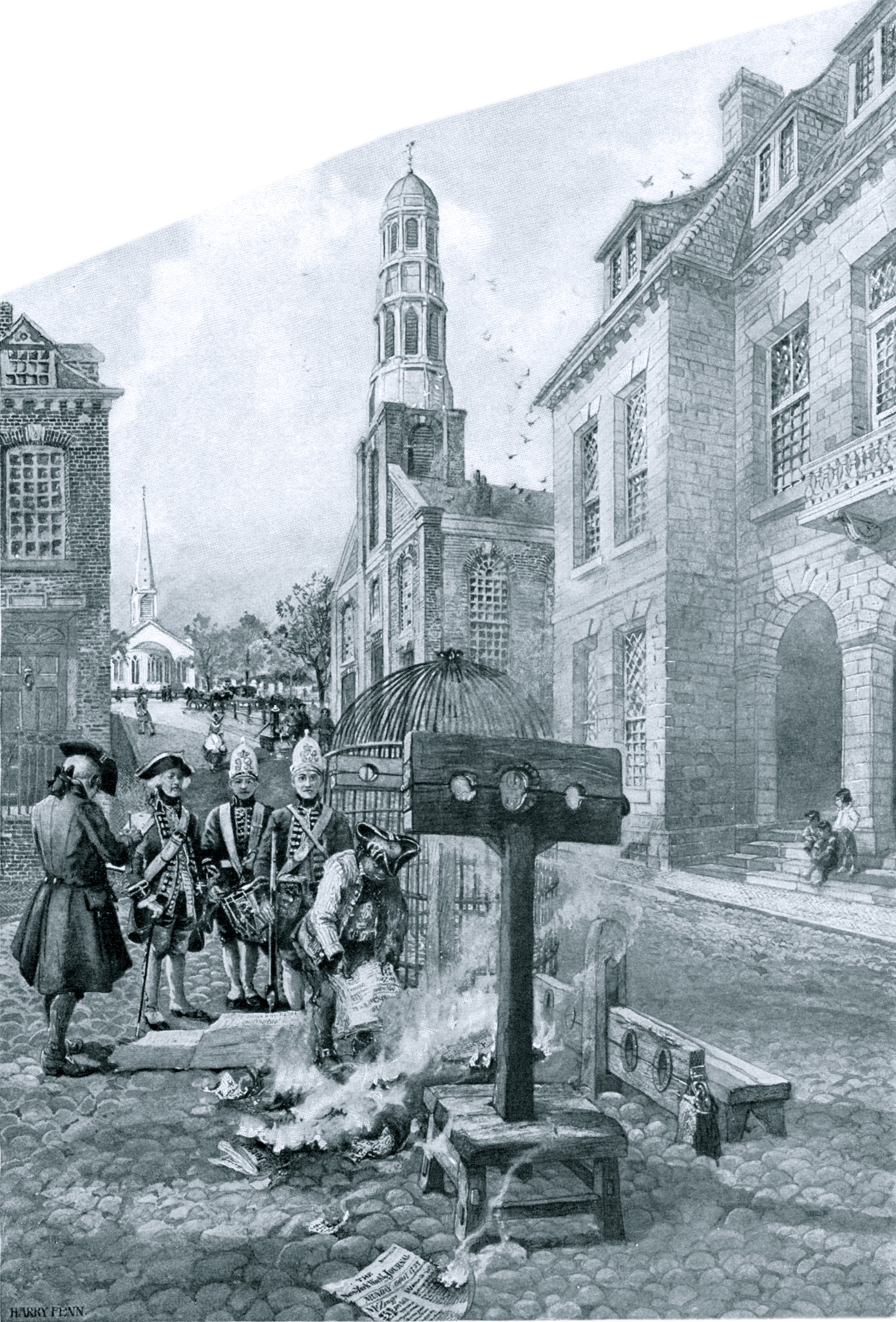

Based on original records and prints in Lenox Library and New

York Historical Society. The buildings to the right are the City Hall and the

Presbyterian Church. The original Trinity Church is indicated in the distance.

The stocks, whipping-post, cage, and pillory are shown at the head of Broad

Street. Illustration drawn by Harry Fenn, published in the Harper's Monthly

Magazine, May, 1908, in the Wall Street in Colonial Times by

Frederick Trevor Hill. Source: New York Public Library. The scene was explained

in the Magazine:

«...Jeremiah Dunbar, the Recorder, was a dignified gentleman whose offices could

be required only for affairs of state, and the paper which he proceeded to read

in stentorian tones demonstrated that he was attending in his official capacity.

(...) a little group of officers sauntered up Broad Street from the direction of

Fort George and paused to learn the occasion of this proclamation to an empty

street. Solemn indeed was the occasion as disclosed by the Recorder, who with

due form and ceremony recited an order of the Council, dated October 17,

1734,

wherein and whereby it appeared that one John Peter Zenger had set up, printed,

and published divers and sundry nefarious matters defamatory of the government

and his Excellency Governor Cosby, in a news sheet or paper known as the New

York Weekly Journal: wherefore it was decreed that certain issues of said

paper, numbered 7, 47, 48, and 49,* should be burned near the pillory at the

hands of the Common Hangman or Whipper [continue below]

1734,

wherein and whereby it appeared that one John Peter Zenger had set up, printed,

and published divers and sundry nefarious matters defamatory of the government

and his Excellency Governor Cosby, in a news sheet or paper known as the New

York Weekly Journal: wherefore it was decreed that certain issues of said

paper, numbered 7, 47, 48, and 49,* should be burned near the pillory at the

hands of the Common Hangman or Whipper [continue below]

*These and subsequent details are

derived from a rare publication in possession of the New York Bar Association,

entitled Narrative of the Case and Trial of John Peter Zenger, issued in London

in 1752.

as

a public warning to the writer and other evil minded persons, and that the

printer should be duly prosecuted for the injurious statements contained in his

sheet. Very little of all this was sufficient to put the Recorder’s slim

audience in touch with the situation, for Governor Cosby’s recent encounter with

the local authorities over the case of the Weekly Journal was

unpleasantly familiar to all the powers that were. Indeed, every one in town

knew that his Excellency had overreached himself by ordering the Mayor and city

magistrates to attend the destruction of Zenger’s paper, and that those

functionaries, quick to resent any infringement of their liberties, had

instantly denied his right to impose any such duty upon them, and flatly refused

to lend their presence to the scene. This angry clash of authority had been

followed by a petition from the sheriff praying that the public whipper be

designated as the person to apply the torch, and when his request had been

denied, the coerced official had appointed a negro slave to act as his deputy,

and the public had decided by common consent to support the local authorities by

shunning the scene of action at the appointed hour.

as

a public warning to the writer and other evil minded persons, and that the

printer should be duly prosecuted for the injurious statements contained in his

sheet. Very little of all this was sufficient to put the Recorder’s slim

audience in touch with the situation, for Governor Cosby’s recent encounter with

the local authorities over the case of the Weekly Journal was

unpleasantly familiar to all the powers that were. Indeed, every one in town

knew that his Excellency had overreached himself by ordering the Mayor and city

magistrates to attend the destruction of Zenger’s paper, and that those

functionaries, quick to resent any infringement of their liberties, had

instantly denied his right to impose any such duty upon them, and flatly refused

to lend their presence to the scene. This angry clash of authority had been

followed by a petition from the sheriff praying that the public whipper be

designated as the person to apply the torch, and when his request had been

denied, the coerced official had appointed a negro slave to act as his deputy,

and the public had decided by common consent to support the local authorities by

shunning the scene of action at the appointed hour.

Such was the explanation of Wall Street’s deserted aspect ;

but Recorder Dunbar was equal to the occasion, and the four offending papers

were duly burned by the sheriff’s humble substitute, to the thorough

satisfaction of the spectators, who gravely watched the flames until the last

scrap was reduced to ashes, and then turned on their heels with an exchange of

formal salutes, Dunbar retiring to the City Hall and the officers to their local

barracks.

It would be difficult to imagine a more childish performance

than this whole proceeding, and even from a childish standpoint it was far from

a success, for the fire was not a good one, and its flames were poorly fed. Yet

of this tiny blaze started in Wall Street in the fall of 1734 came a mighty

conflagration which wellnigh lit a world.

John Peter Zenger, whose editorial pages were thus cleansed

with fire, was not the ablest journalist of New York, and Governor Cosby, whose

administration he attacked, was not its worst Executive. The whole history of

the city, however, had long been an inglorious recital of greed, corruption,

incompetence, and arrogance, the royal governors having included a gentleman who

made the seaport the most desirable of all piratical resorts; a noble personage

who took pleasure in masquerading in women’s clothing and exhibiting himself in

this guise, with the pleasing delusion that he might be mistaken for Queen Anne;

and a solemn nonentity who took himself so seriously that he exacted more

deference and reverence than would have been accorded to his royal master. In

fact, all the powers that were, including the landed gentry and the personal and

political favorites of the provincial court, displayed an undisguised contempt

for the masses, affecting an elegance of attire in which dress swords, ruffled

shirts, silk stockings, and short clothes served to emphasize the class

distinctions. Not all the members of this little aristocracy, however, were

Englishmen, for no more proud or exclusive dignitaries ever strutted than the

Dutch patroons, and when the ponderous travelling coach of one of those lords of

the manor lumbered down Wall Street’s cobbled roadway, on official business

bent, there were few who disdained to court recognition, while the populace

frankly stared with admiring wonder, many of them cap in hand.

It was this condition of affairs that had brought Zenger to

the front as the nominal editor and publisher of the Weekly Journal,

which had really been established and was mainly supported by James Alexander

and William Smith, two able lawyers, under whose active leadership a popular

party was rapidly forming.

Zenger himself was a young man of more courage than education,

whose boldest utterances read very mildly in these days of unbridled

denunciation, but any criticism of official actions was then regarded as

presumptuous, and his shafts evidently hit the mark, for the destruction of his

pages had been planned as a most impressive ceremony, and the humiliating fiasco

which resulted, virtually forced the government to take further proceedings in

defence of its dignity. Within ten days, therefore, Zenger was arrested at the

instance of Governor Cosby and lodged in jail, where he remained for many months

in default of excessive bail. Meanwhile the public began to take an

unprecedented interest in the affair, and under the energetic leadership of

Alexander and Smith such a strong sentiment was aroused in favor of the accused

that the Grand Jury refused to find an indictment against him, and the

Attorney-General was compelled to resort to extraordinary measures to prevent

his release. This merely intensified the popular feeling, however, and before

long all the scattered opponents of the government rallied to the slogan,

“Freedom of the Press!” and united in supporting the imprisoned editor, whose

cause immediately became a political issue of far reaching effect.

Never before had the general public been identified with any

determined effort to secure freedom of the press in America, and far seeing men

throughout the country, including Benjamin Franklin and other aspiring

journalists, watched the struggle with keen interest, while in New York the

opening moves of Zenger’s counsel resulted in such sensational developments that

the public excitement was kept at the highest pitch.

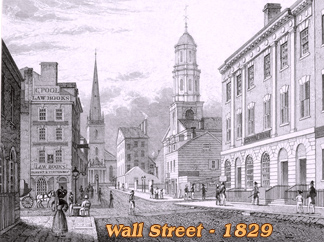

The City Hall, where Zenger had been confined, was far from a

triumph of architecture, but it was dignified and spacious, affording

accommodations for a court room, a jury room, a Council chamber, a common jail,

a library,* and a debtor’s prison, to say nothing of space reserved for the fire

department, whose water supply was partially obtained from two Wall Street

wells; and it was here that the lawyers for the defence began the proceedings

which were destined to assume historic importance...»

*Wall Street was

never a literary centre, but it housed the first collection of books known to

the city. This library subsequently became the Corporation Library, and

eventually the New York Society Library, which exists to-day.

More: Wall Street in

18th century

►

1734,

wherein and whereby it appeared that one John Peter Zenger had set up, printed,

and published divers and sundry nefarious matters defamatory of the government

and his Excellency Governor Cosby, in a news sheet or paper known as the New

York Weekly Journal: wherefore it was decreed that certain issues of said

paper, numbered 7, 47, 48, and 49,* should be burned near the pillory at the

hands of the Common Hangman or Whipper [continue below]