Wired Cityscapes in New York City - 19th Century

In the 1880s, the former beautiful cityscapes in New York City were severely damaged by the large number of utility poles and overhead wires and cables. They ran services like telegraph, telephone, signaling, lighting and electric power. On major thoroughfares, such as Broadway, there were many hundreds of them, resulting in unsightly views. The first utility poles and overhead wires in New York City were launched in 1845 for telegraph services. In 1904, the last overhead wires were removed in the Borough of Manhattan.

First there were telegraph wires. Visual signals, as a type of long-distance communication, have existed in human history for millennia. In New York, visual telegraph was used long before the electric version arrived. In 1812, for example, the Common Council "Resolved that the committee of defence be directed to take measures for procuring a Copy of the Signals to be used at the Telegraph at the Narrows also a good Glass and the necessary Utensils and fixtures to give the same Signals from the Cupola of the City Hall" (from the Minutes of the Common Council). On May 14, 1813, "The Telegraph on Staten Island displayed, at 12 o’clock this day, four black and two white balls, indicating the approach of four ships of the line and two frigates" (Com. Adv.). In 1821, a new system, using symbols for the alphabet, was tested in New York. By 1830, there was a telegraph station at the Merchants' Exchange in Wall Street, which housed the post office, that could receive messages from Staten Island, and another was established in 1837 on Holt's Hotel.

The first electric telegraph line began to be laid in 1843, between Washington and Baltimore. It was initially underground, but the line was failing. Then, on April 1, 1844, the line began to be constructed using poles. Wires were attached by glass insulators to poles alongside a railroad, 60km long. It was operational in May, 1844.

In 1845, in New York City, there was a magnetic telegraph operating in the postmaster’s room in the Post Office established in the old Middle Dutch Church, by which messages were sent to and from the Branch Post Office in Chatham Square, and also to his residence in Eighth Street, which was about two miles from the office.

In May 1845, Samuel Morse, famous for his code, formed the Magnetic Telegraph Company with other investors. Its telegraph office was opened in a small basement room at 46 Wall Street. On August 6, the Common Council permitted “the proprietors of Morse’s Electro-Magnetic Telegraph to set posts for the purposes of said Telegraph along the line of the side-walks,” under the directions of the street commissioner. That year, this and other companies were in a frenzy to build telegraph lines.

In 1844, there was a telegraph station at Coney Island, probably operating via a semaphore telegraph. In October, 1845, the Morse's New York and Offing Electro-Magnetic Telegraph Company (Colt & Robinson) began to building a telegraph line from their office in Dorr's Granite Building in Exchange Place (rear of the Merchants' Exchange) to an observation tower in the westernmost point in Coney Island to get news from shipping traffic for subscribers to the "Telegraphic Bulletin and Foreign News Room" in advance of every other means. On November 6, 1845, the New-York Daily Tribune published the following news: "The workmen have finished putting up the wires for the Coney Island Magnetic Telegraph. How they are going to get the news across the East River does not yet appear". The wires were laid across the East River, from Fulton Ferry, on NY side, to Fulton Ferry, on Brooklyn side. The telegraph station in Brooklyn was in the corner of Everit and old Fulton streets, near the ferry. Unfortunately, the wires were torn up by an anchor and they were laid again on November 10. The first part of the line was completed before November 26 (New York Herald). This telegraph line was operational in January, 1846. In May, the legislature incorporated the New York and Offing Magnetic Telegraph Association.

On December 1st, 1845, the telegraph line, from Nantasket Head (south Boston) to the Merchants' Exchange was nearly completed (New York Herald, December 4). It seems that telegraphic communication between Boston and New York City was not operational before July, 1846.

In 1846, telegraph lines ran from New York City to Philadelphia, Boston, Albany and Washington. A view of Wall Street, dated 1846, represents a telegraph line with overhead wires.

By 1851, ten companies operated telegraph lines lines in New York City: three competing lines between New York and Philadelphia, three between New York and Boston, and four between New York and Buffalo. That year, the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company, later Western Union, was organized in Rochester, New York.

In August, 1858, the first transatlantic telegraph cable was inaugurated, connecting North America to Ireland. The venture was led by Cyrus W. Field (1819-1892), one of the founders of the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company, formed in 1852 and incorporated in 1854 to carry out the project. The first transatlantic telegraph cable was celebrated with a parade on Broadway. Unfortunately, the cable never worked well and eventually failed. A permanent transatlantic cable finally succeeded in 1866.

In the late 1860, the Western Union began its dominance. The company handled 9 million messages in 1870, 29 million messages in 1880 and 56 million, in 1890. By this time, the telegraph boom was over.

A new technology had arrived: the telephone was patented in 1876 by Alexander Graham Bell as "Improvements in Telegraphy". The same year, the Telephone Company of New York was formed under franchise. The company rented telephone sets and users were expected to provide wires to connect them. In 1878, the Bell Telephone Company of New York was organized. Telephone numbers were introduced in the city in 1880.

In the early years, telephone was only used for local calling. The first long-distance telephone line in the world was constructed, between New York and Boston, in 1884. In 1885, a line connected New York to Philadelphia and, in 1892, New York and Chicago were connected by phone.

Then electric light arrived in New York.

On November 9, 1880, the N.Y. Times reported that the United States Electric Lighting Company had introduced their arc and incandescent lights in the offices and vaults of the Mercantile Safe Deposit Company, in the basement of the Equitable Building. This was said to be the first practical use of the incandescent mode of lighting.

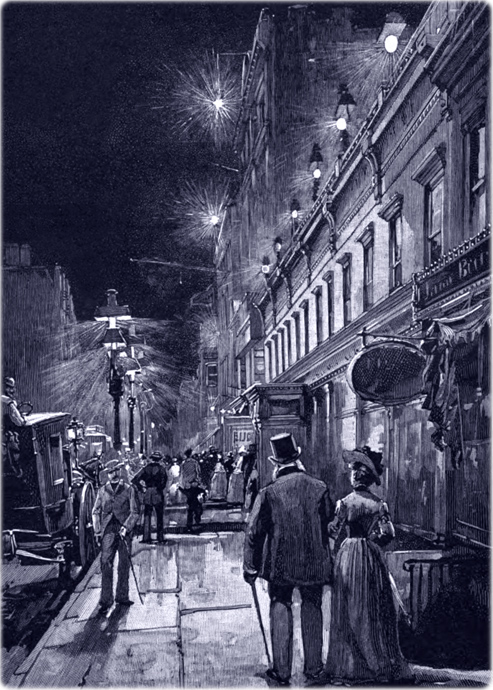

On December 20, 1880, arc lamps were installed on Broadway by Brush Electric Light Co., from 14th Street to 26th Street and Madison Square, the lights being placed a block apart. In the same day, at Menlo Park, an exhibition of the Edison electric light system was given for members of the Common Council.

On July 1st, 1881, the N.Y. Times reported that poles were being set up under the elevated railroad structure in Bowery, by Brush Electric Light Company, for the support of the wires intended for the general distribution of their "lighting power". The line began at the Brush Company’s station, 9o Walker Street, extended up the Bowery and Third Avenue to 14th Street, thence to Broadway and Fifth Avenue where two branches were formed, one running up Fifth Avenue to 34th Street, and the other up Broadway to 42nd Street. The power for the Bowery line would be partly supplied from a station at 640 Broadway. Another line, supplied partly from the Walker Street station and partly by a station at 48 Washington Street, would be run down Broadway to the Battery and connect with Pier 1 North River, where Brush lights was already supplying electricity to the Iron Steam-boat Company. These lines were intended not to light the streets, but to furnish electricity for private purposes.

The station of Thomas Edison’s electric company, at 257 Pearl Street, began to supply the financial district on September 4, 1882. The wires were laid underground. The company had 513 customers in 1883.

In December 1882, incandescent lights were used by Mr. Johnson in his Christmas tree. There were also other private electric power stations in businesses and homes. By 1893 there were 1500 arc lights illuminating New York streets.

In the late 1880s, overhead wires were everywhere, lots of them. The result was an ugly forest of wires and poles. Their removal was a tough task. In 1852, telegraph posts were ordered to be removed from Broadway, according to the Evening Post (September 9, 1852). On July 29, 1880, the Daily Graphic wrote that overhead telegraph wires on Broadway and elsewhere disfigured the City.

On March 13, 1883, the board of aldermen, by a vote of 21 to 3, authorized the N. Y. Electric Lines Co. to tear up the streets of the city and to lay telegraph wires underground, on condition that the company pay the city 2% of its gross receipts. This was vetoed by Mayor Edson, on March 27, but it was passed over the veto on April 10.

On June 14, 1884, the legislature passed the "subway act", requiring that “all telegraph, telephonic and electric light wires and cables” should be “removed from the surface of all streets or avenues” before November 1, 1885. Unfortunately, it did not work and a second subway act was approved on June 13, 1885, creating the Board of Commissioners of Electrical Subways in the City of New York with authority to execute the plan. This act was emended by the act of May 29, 1886.

On September 3, 1886, the first conduits for putting the telegraph wires underground were laid, before a large crowd of people (N.Y. Times, September 4).

On June 25, 1887, the Board of Electrical Control was created by Act of the legislature. Its powers and duties embraced the subjects of construction, maintenance, and control of electrical conductors, and their conduits or subways. Except by permission of this board, no poles or wires could hereafter be erected or retained above ground. The removal of wires and poles was accomplished without expense to the City but the process took several years.

The myriad overhead wires in the streets of so crowded a city as New York were not only unsightly, but a source of considerable danger in many ways. They also interfered with the firemen's work. The City's decision to remove all overhead wires was reinforced after the Great Blizzard of March 1888, when many utility poles fell due to the storm, the City went dark and people died after stepping on the wires covered by snow.

The United States Illuminating Company sued the Board of Electrical Control in its fight to avoid putting its wires underground, but the Supreme Court decided against the Company on January 2, 1889.

According to Stokes (Iconography of Manhattan Island, ...1926), based on proc. from the Board of Aldermen, on January 7, 1889, electric wires and telegraph poles continued to disfigure the streets and obstruct the thoroughfares, notwithstanding the general demand for the burial of the wires.

On April 12, 1889, Judge Wallace of the United States Circuit Court dissolved the injunction granted to the Western Union Company forbidding the Board of Electrical Control to interfere with its poles and aerial wires. In the following days and axe brigade moved quickly through the city, cutting down the poles and the utility companies were rapidly laying their wires into the subways.

Eventually, in the year 1889, a large amount of poles were removed and the wires went underground, specially in Broadway, Union Square and Madison Square. On January 6, 1890, the Mayor informed that since January, 1889, the "bureau of incumbrances" had removed 2,495 telegraph poles and about 14,500,000 feet of electric wires, and it was “confidently believed that every pole will be removed from the streets and that every electrical wire will be operated under ground in properly constructed subways” "by the end of next summer". But the removal of overhead wires continued in the following years, until 1904. Under the direction of the Board of Electrical Control, hundreds of miles of subways for telegraph and telephone wires and hundreds of miles of subways for electric light and power cables, were constructed.

In 1904, the removal of the line of telephone poles on West Street, Tenth and Eleventh Avenues, and Broadway, marked the disappearance of overhead wires in the Borough of Manhattan (Message of Mayor McClellan to the Board of Aldermen, January 2, 1905).

Disorderly wires about to be cut down on Lower Broadway, looking north from near Corbin Building (192 Broadway), corner of John Street (Illustration from Harper's Weekly July 27, 1889).

Electric lights connected from underground in Manhattan (Illustration from Supplement of Harper's Weekly July 27, 1889).

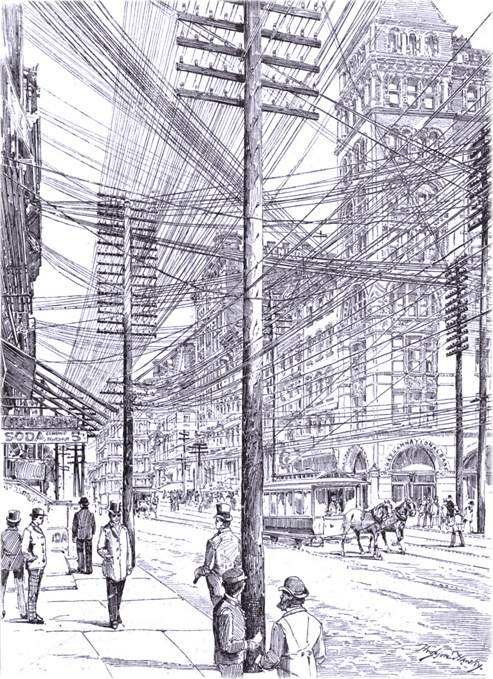

A jungle of utility poles and overhead wires on Broadway, about the late 1880s. Buildings on the west side and corner of Cortland Street.

Removing telegraph poles in Union Square (Illustration by W.A. Rogers, from Harper's Weekly April 27, 1889).

Wired Cityscapes in New York City - 19th Century

By Jonildo Bacelar, Geographic Guide editor, July 2023.