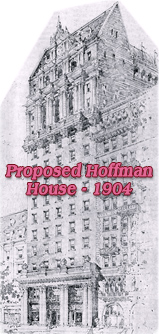

Original title: The New Hoffman House and the Old Albemarle

Hotel. Broadway and 24th Street, New York. Photo published in The

Architectural Record, issue October 1908, in the section "Architectural

Aberrations", with the following text:

«For these many moons must passers along Broadway and tramps resting for a space in Madison Square have been marveling at the disjecta membra of the new Hoffman House, disjected by the retention of the ancient and honorable Albemarle Hotel standing between them. Truly it has seemed to such of the passers and tramps as were blessed with architectural sensibility that it stood between them “that the plague might be stayed” and the completion of the new and formidable Hoffman House be delayed.

Is there any antiquary to tell how old the Albemarle really is? Those ancient inhabitants who have been taking the occasion of the threatened demolition of the Fifth Avenue Hotel to recall how they had played tag or attended circuses and ridden elephants on its site might advantageously prod their memories about its humbler neighbor, and tell us not only when it was built, but who was the architect of it. For it is manifest that it had an architect. The Fifth Avenue by no means made such a manifestation. There was nothing in its aspect to denote that anybody above the pretensions of the common builder had anything to do with its design. As a matter of fact, the Fifth Avenue had an architect, and the most fashionable architect of his generation it was, Griffith Thomas, to wit, the author of the brownstone fronts on the other side of Madison Square. True, he did not waste any of his brains, such as they were, on the design of the hotel. He simply adjoined and coagulated a number of twenty-five-foot brownstone fronts, five stories high, transformed the veneer from brownstone into white marble, and let it go at that. An amusing instance of the thoughtlessness of the so-called design is that after every third window there is a wider pier of wall than the intermediate piers. In a row of houses this thickening is of course obligatory, by reason of the party wall. In a hotel it has no meaning at all. But it is all the “architecture” the Fifth Avenue had to show, excepting the detail of the window openings, which might have been and probably was taken bodily out of a builder’s manual of the period, and excepting the umbrageous sheet-metal cornice.

The Albemarle may have been a little older or a little younger than the Fifth Avenue. Not much of either. It was certainly standing during the Civil War, and as certainly was then new. But even now you cannot help seeing that it had an architect, and that he was of some sensibility and of some cultivation. That was more “evidences of design” than were afforded by any other hotel on Broadway in those days until you got two miles below to the Astor House. Between were the brownstone St. Nicholas and the brownstone Metropolitan, each as innocent of architecture as the Fifth Avenue, and the Prescott House, of which the vulgarity attested the complicity of an outrageous “artchitect” instead of the unpretentious builder. Soon after came the outrageous castiron Gilsey House, a few squares above the Albemarle, in which the “artchitect” stood not only confessed, but proclaimed. Until the Hotel Imperial was built the Albemarle had no rival on what then was “upper” and now is “middle” Broadway.

The architectural points of the Albemarle, though few and simple, were decisive. It showed more wall than any other hotel since the Astor House. Moreover, the weight of the wall was in the right places. Standing the whole Broadway front on a sheet of plate glass is a subsequent nuance. As built, it showed the preference of the designer for a wall solidest at the ends and lightest in the middle, as you may still see on the Twenty-fourth Street front, where the ground floor is still architecturally reinforced at the ends. It is true that, above the ground floor, the terminal piers are weak and ineffectual. But you also see that the architect recognized this as a misfortune and tried to dissemble it. And then, vertically, the thing has a beginning, a middle and an end. The beginning is the basement made as solid as the architect dared to make it. The middle is the four stories, variegated and punctuated with the little balconies, well placed for punctuation and reasonably well designed and with intervals of wall between, which intervals the windows are coupled to “effectuate.” The end is the two-story mansard, which also was quite a feat of architecture in the New York of i860. The fenestration of that Broadway front is, in fact, very good. And the acute angle of the corner is very effectively signalized by the large single opening in each story, with, on either side, a sufficient flank of wall. Truly the thing was quite a wonder in the Broadway of 1860. And among the most recent of the skyscraper hotels, it would be hard to designate one which surpasses it in the article of architectural brains. Whoever did it must have had his sensibilities and his perceptions. For its time, it smacked of Paris “in partibus.”

At all events, it is not the kind of

thing that the sensitive and perceptive observer likes to see treated with

“wantonness of insult.” And that is just the way in which it has been treated by

the projectors of the two fragments of the new Hoffman House which enclose it.

The melancholy and ridiculous spectacle which the two towering wings of the

modest old caravenserai present violently recalls the Scriptural story of

Naboth's vineyard. It does not, indeed, appear that “Jezebel" has intervened in

the modern instance. But there is evident intention, on the part of the modern

flanker, to make Naboth's quarters too hot to hold him. By strictly legal means,

of course, and in the exercise of the riparian owner's rights to do what he

wills with his own. As old Coke hath it, the thing has been done “ever under the

protection of the law and in the gladsome light of jurisprudence.” About the

circumvallation there is a circumspection as of the circumcision to avoid legal

pains and penalties. But, all the same, the two absurd brick towering

parallelopipeds do so overtop, insult, domineer over and threaten poor Naboth,

and warn him to get out, that they are tantamount to a public provocation to a

breach of the peace. Ahab, coveting Naboth’s vineyard, has not scrupled, in his

encompassing and overtopping and threatening architecture (if we may use that

expression) to indicate to Naboth that he was waiting until he got Naboth

extruded in order to complete his nefarious work. The dullest wayfaring man

along Broadway, though he might imagine that the instalment of the new Hoffman

House, which he sees down the side street, might be complete in itself, could

not possibly make that supposition about the instalment on Broadway. For that,

as it now stands, is avowedly and outrageously unsymmetrical and lopsided. Let

us assume that that vertical slice which contains the big bow-wow portico at the

door, the big bow-wow corbelled balcony over, the big bow-wow balcony over the

impossible protruding arch, and the big bow-wow broken pediment, relieved

against the “attic,” means something. This vociferous slice of architecture

seems to proclaim a special purpose. The wayfaring man, perceiving this,

hypothecates as the special purpose the frontage and expression of a corridor.

By the hypothesis the corridor gives upon rooms on both sides. But in present

fact there are evidently rooms only on one side. The “feature” manifestly exists

in prevision of the time when the machinations of Ahab shall be successful and

Naboth’s vineyard shall have "fallen in.” Could anything be more infuriating to

Naboth? Can we not overhear him soliloquizing:

At all events, it is not the kind of

thing that the sensitive and perceptive observer likes to see treated with

“wantonness of insult.” And that is just the way in which it has been treated by

the projectors of the two fragments of the new Hoffman House which enclose it.

The melancholy and ridiculous spectacle which the two towering wings of the

modest old caravenserai present violently recalls the Scriptural story of

Naboth's vineyard. It does not, indeed, appear that “Jezebel" has intervened in

the modern instance. But there is evident intention, on the part of the modern

flanker, to make Naboth's quarters too hot to hold him. By strictly legal means,

of course, and in the exercise of the riparian owner's rights to do what he

wills with his own. As old Coke hath it, the thing has been done “ever under the

protection of the law and in the gladsome light of jurisprudence.” About the

circumvallation there is a circumspection as of the circumcision to avoid legal

pains and penalties. But, all the same, the two absurd brick towering

parallelopipeds do so overtop, insult, domineer over and threaten poor Naboth,

and warn him to get out, that they are tantamount to a public provocation to a

breach of the peace. Ahab, coveting Naboth’s vineyard, has not scrupled, in his

encompassing and overtopping and threatening architecture (if we may use that

expression) to indicate to Naboth that he was waiting until he got Naboth

extruded in order to complete his nefarious work. The dullest wayfaring man

along Broadway, though he might imagine that the instalment of the new Hoffman

House, which he sees down the side street, might be complete in itself, could

not possibly make that supposition about the instalment on Broadway. For that,

as it now stands, is avowedly and outrageously unsymmetrical and lopsided. Let

us assume that that vertical slice which contains the big bow-wow portico at the

door, the big bow-wow corbelled balcony over, the big bow-wow balcony over the

impossible protruding arch, and the big bow-wow broken pediment, relieved

against the “attic,” means something. This vociferous slice of architecture

seems to proclaim a special purpose. The wayfaring man, perceiving this,

hypothecates as the special purpose the frontage and expression of a corridor.

By the hypothesis the corridor gives upon rooms on both sides. But in present

fact there are evidently rooms only on one side. The “feature” manifestly exists

in prevision of the time when the machinations of Ahab shall be successful and

Naboth’s vineyard shall have "fallen in.” Could anything be more infuriating to

Naboth? Can we not overhear him soliloquizing:

In some region wild and woody,

I would like to punch your head,

Old Solomon Nathan Moody.

Nay, if Naboth were greatly enough moved to punch the head of Ahab, when he espied him on Broadway, between Twenty-fourth and Twenty-fifth, gloating on the ruin he had wrought, what feeling heart among us, if it were impaneled on the jury, would consent to finding Naboth guilty of any offence whatever? And yet Naboth would be, legally entirely in the wrong, since Ahab, legally, is entirely within his rights in encompassing and overtopping Naboth and putting him under compulsion to sacrifice his holdings at ruinous rates and flee into the wilderness! Evidently the law maxim, “So use your own that you do not injure another,” is subject to new and strange interpretations in the New York of 1908!

This sort of thing is going on everywhere and all the time. It is a consequence of “the march of improvement.” But here it is done with so peculiar and impudent a cynicism that the instance fairly clamors for notice. Not many modern erections are intrinsically more inartistic and absurd than this of the two wings of the new Hoffman House. And yet what is most flagrant about them is not their intrinsic inartisticality and absurdity, but the brutality with which they hem in and bully the mild, discreet and gentlemanly old edifice between and beneath them. It is a crucial instance of unneighborliness, of want of comity, of “incivism.” Wherefore it is worth the affix of a stigma.»