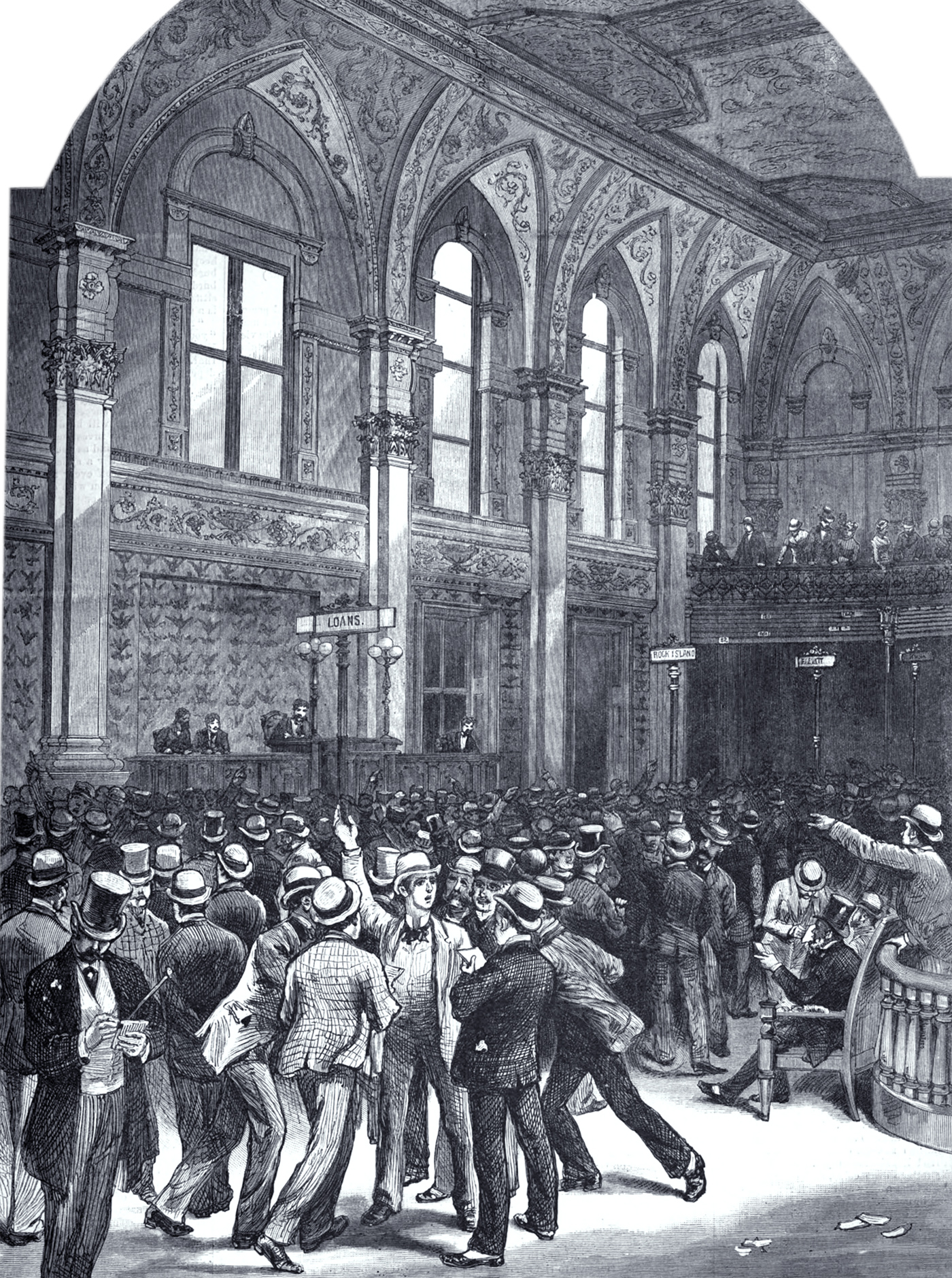

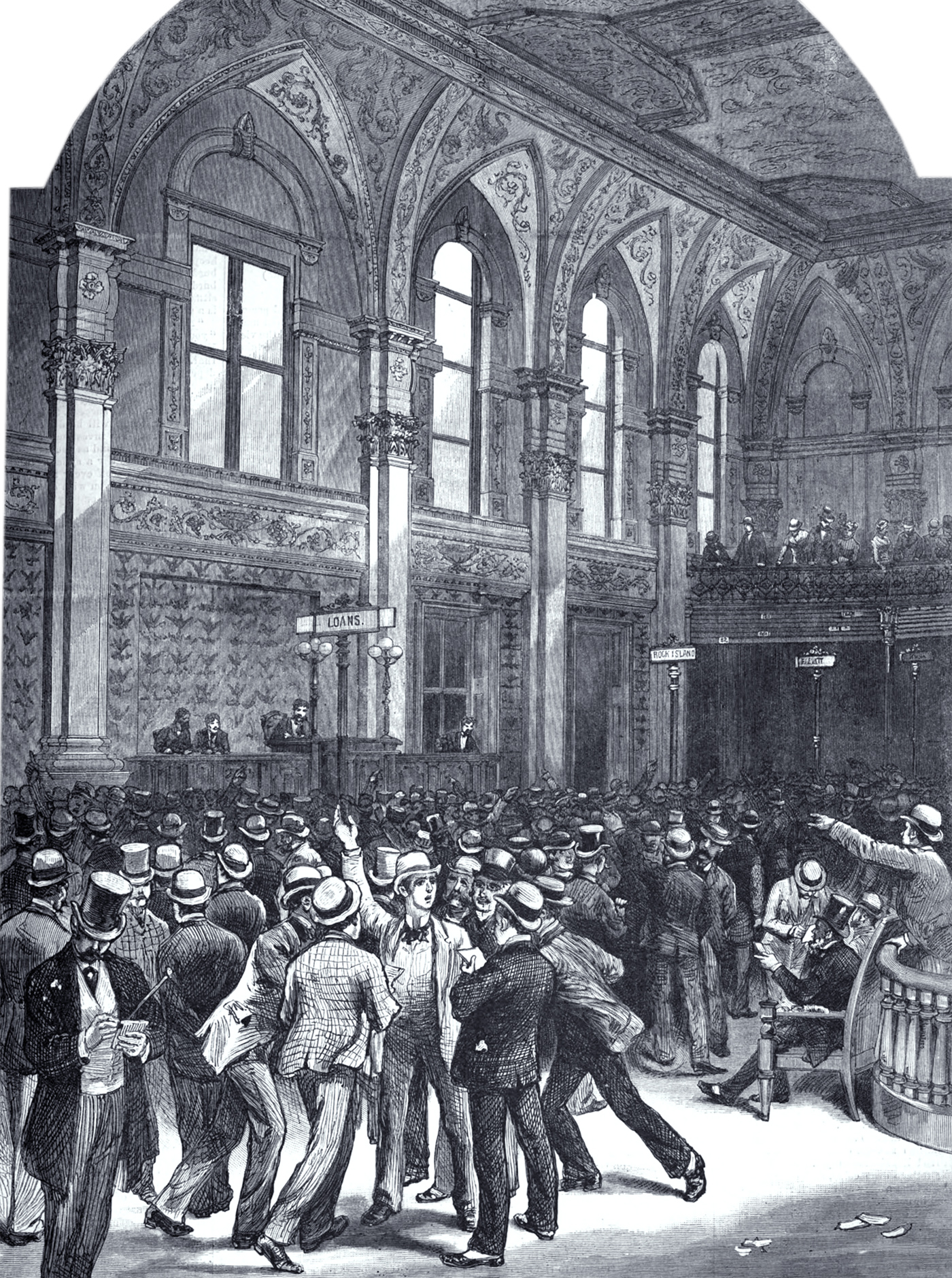

Stock Exchange Trading Floor - 1881

The New York Stock Exchange trading floor in 1881. Illustration drawn by Graham and Thulstrup, published in Harper's Weekly. Journal of Civilization. Issue September 10, 1881.

The NYSE moved to this old building in 1865 and traders worked in it until April 1901, then the building was demolished to make way for the present Greek-style edifice. The trading room of this old building was enlarged and expanded two times: in 1871 and in 1881. Below, text that accompanied the engraving above, from Harper's Weekly:

«WHEN in 1865 the New York Stock Exchange erected its building on Broad and New streets, just out of Wall, the members thought that they had made ample provisions for the future. They had a five-story building, with a frontage on Broad Street of forty-five feet and a depth of eighty-eight feet, with a T on New Street eighty by sixty-eight feet. This building was divided into suitable rooms, the most important being the Board Room, which was fifty-three feet wide and seventy-four feet long. This seemed a large enough room. There were in the Exchange then 400 members, and although the price of a seat in the Exchange was but $3000, it was not expected that in sixteen years the membership would be nearly three times as great. But to-day there are 1100 members of the Stock Exchange, and the price of a seat has risen steadily, until $34,000 has been recently paid. This increase in membership, and consequent increase in resources, led the members to think of increasing their facilities for doing business. The old building was daily proving inadequate. Not only was it not large enough to accommodate the members, but it was not large enough to accommodate the hundreds of telephones, telegraph instruments, and “tickers” that have so multiplied within the last ten years.

It was decided to enlarge their quarters. A building committee, composed of Donald Mackay, President of the Stock Exchange, A.M. Ferris, Vice-President of the Stock Exchange Building Company, Howard Lapsley, and Frank Sturgis, took the matter in hand. The committee bought on Broad Street, adjoining the Stock Exchange Building, a lot twenty-four feet wide and eighty-six feet deep, and on New Street they bought a lot sixty-eight by seventy-two. This increased the frontage on Broad Street one-third, and doubled the New Street frontage. Then began the work of adding to the old building, and making of both new and old one symmetrical and convenient whole. It was a work requiring considerable more architectural skill than to build a new building. James Renwick was the architect to whom the work was given. An inspection of the building as it stands to-day shows just how successful he has been. The old Broad Street front was taken down, the interior changed in many particulars, and now the Exchange has a building that is apparently very complete. Work was begun in June, 1880. To-day the painters are putting the finishing touches on the walls and wood-work of the interior. The Broad Street front is sixty-nine feet in width, and from the sidewalk to the top of the cornice of the fifth story the distance is 101 feet, and to the top of the French roof 120 feet. The front is of marble, elaborately carved in the French Renaissance style. The portico of the first story has eight polished and carved red granite columns flanking the three windows and two doors. The key-stones to the windows and doors are richly carved, with the heads of Fortuna and Plutus in bass-relief, surrounded by foliage, flowers, and fruits. The portico projects four feet from the front, and bears in large letters the words “New York Stock Exchange,” cut in the frieze. The central pediment has a very richly carved tympanum. The four stories above the first have each five windows, and in the central tympanum of the fifth story is a carved shield, with the monogram of the Exchange cut upon it. The work on the building has now cost $275,000, and will reach nearer $300,000 when everything is completed.

Entering by the right-hand door, one passes into the Long Room—a department devoted to telegraph desks, messengers’ desks, and seats for subscribers. There has been no change made in the Long Room, which is forty feet wide by sixty-nine feet long. Parallel with this, and entered both from the street by the left-hand door and from the Long Room, is a large apartment, thirty-two feet wide and sixty-six feet long, elegantly finished in black walnut, elaborately frescoed, and which will be very carefully furnished, for it is to be the smoking and lounging room of the members of the board, and none but a member will be admitted to its pleasant precincts. The attractions of this room are two huge fire-places of yellow Echaillon marble, carved in the most approved Renaissance style. From flourishing foliage drop coins, and over the head of Fortuna a bear and a bull rampant contend in battle.

Back of these two rooms runs at right angles a long passage to Wall Street. It is twenty-four feet wide here, and gives ample room for scores of telephones that hang in rows along the walls. From this passage many swinging doors open into the great Board Room, the room of the building. There is not such another in this city certainly. It is 140 feet long, fifty-four feet wide, and from the floor to the lofty panel of the iron ceiling is fifty-five feet. Two tiers of windows open upon New Street, and give abundant light. Under these windows run railings, behind which messengers wait in business hours. At each end of the room is another railing, behind which subscribers can congregate, and communicate with the brokers upon the floor. On each side of the huge room rise ten great red granite pilasters, with marble bases and bronze capitals. These pillars are thirty-five feet high, and from the cornice over them the ceiling is groined for twenty feet, as far as the centre panel. The effect is good, for there is the appearance of strength and gracefulness combined. At each end of the room is a gallery, from which visitors can look down upon the conflicts between bulls and bears in the arena below. The President’s desk is on the east side of the room. The board prefers to retain the old one, which is massive, and dark with age. The walls and ceiling are painted in the richest and most elaborate style of Renaissance decoration. Blue and gold are the predominating colors, but by no means the only colors; for in painting the arabesques of flowers and foliage, and the fabulous beasts of the Renaissance, all the colors of the rainbow are used, and some not in the ordinary every-day rainbow.

Having paid his $34,000 for a “seat” in the Exchange, the member finds that he has no seat. The floor of the Board Room is destitute of seats, save a few here and there around the walls. There is nothing to impede the course of the members in their struggle with fortune, save a row in the centre of six small iron posts seven feet in height, each bearing the name of some stock which is dealt in. For instance, one post bears on one side the name, “ Western Union”; on the other, “ Wabash Common.” Then at different points on the walls are cards with the names of other stocks upon them. These are guides for the members. If one wishes to deal in Western Union, he sees on entering the room the card, and near he finds the men who are dealing. He hurries up to the group, which may be idly talking at that moment, and shouts the figure that he will give for 100 shares. Instantly there is a commotion. Half a dozen men yell at him the figure that they will take; others join in bids. They shake their fists at each other; they reach after each other’s hands; they crowd and push, and yell and vociferate. Such a scene in such a group the artist has depicted in the illustration upon page 613 [illustration above]. He gives the action well, but he can not reproduce the noise. But multiply this group by ten, fifteen, or twenty, and then imagine the noise that goes up among the blue and gold and fruits and flowers of that gorgeous ceiling on a “lively day in the street.” Visitors lean over from the galleries and wonder at the tumult below. They can not catch a word that is said, nor can they see a reason for the tumult. They see two men who are gesticulating in a throng grasp each other’s outstretched fingers, then suddenly subside, step back, mark upon a small pad, tuck the memoranda in their pockets, and then perhaps rush over to another group, and go through similar operations. That simply means that Mr. Bull has sold, say, 200 shares of Wabash Common to Mr. Bear for 483, or whatever the price may be, and that each has made a memorandum of the transaction. At such a time the floor of that big room presents a remarkable sight. Crowded with struggling men, some with blanched faces as they see their fortunes slipping from them, a hoarse tumult of discordant cries goes up with a cloud of dust raised by the shuffling feet. The floor is white with bits of paper—torn memoranda or notes of reference or instruction. Messenger boys, gray-coated and white-capped, dart hither and thither through the throng. Anxious messengers and subscribers hang over the railings endeavoring to catch the eyes of struggling brokers. There is nothing elsewhere like the scene.

Formerly there was another element added to the confusion. A broker being wanted by a subscriber, a messenger walked through the room, calling his name in a tremendous voice. The effect was curious, this monotonous, steadily repeated cry arising amidst the tumult of the brokers. Now this is done away with. In front of each visitors’ gallery are series of disks of iron, painted black. They are on hinges, and when they fall on their hinges they disclose under them numbers in white that may be read the length of the room. To each broker is assigned a number; this number corresponds to his name. The disks are worked by electricity, by an operator outside of the room. Say that President Mackay’s number is 10. A messenger wishes to communicate with him. He goes to the operator of the disks and makes known his wishes. The operator touches a button, and in the Board Room a falling disk reveals a big white 10 on a black ground. President Mackay sees it, and knows that he is wanted at the railing. This simple arrangement will do away with much of the noise of the room.

There is nothing above the Board Room but the roof. It occupies all of the New Street frontage. The remaining stories of the building are in the Broad Street building proper. On the second floor is the Government Room, a fine large apartment, forty by seventy feet, hung with crimson cloth, amphitheatrical in arrangement, furnished with massive leather-cushioned chairs, where government bonds are sold. Besides this, there are the President’s and Secretary’s rooms. The three other stories are divided each into six committee rooms. The halls and rooms are finished in ash, frescoed finely, and well lighted. In the basement are safe-deposit vaults, rooms for messenger boys, and complete steam and ventilating apparatus.»

Stock Exchange Trading Floor - 1881

|

Copyright © Geographic Guide - Old NYC Architecture. |