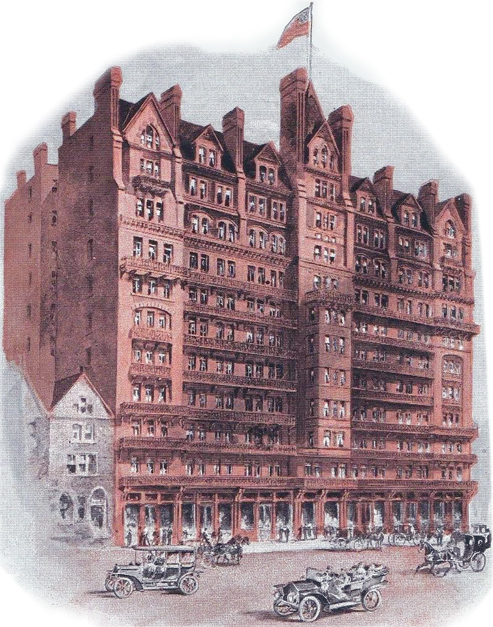

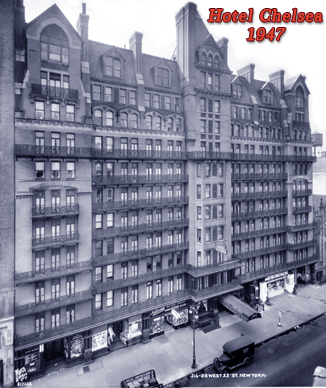

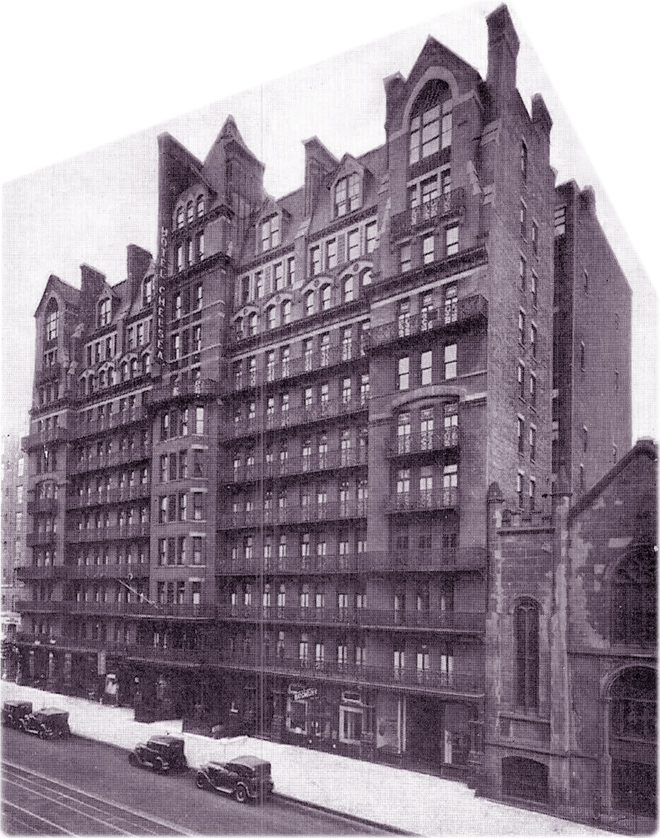

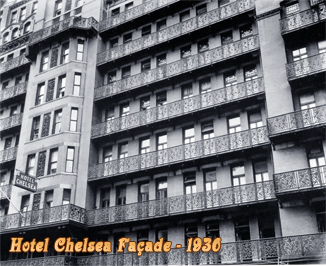

The historic Hotel Chelsea, located at 222 West 23rd Street, between 7th Avenue and 8th Ave., in the neighborhood of Chelsea, is one of the remaining Victorian Gothic apartment houses in New York and one of the early skyscrapers in the City. Before 1905, it was commonly referred to as "The Chelsea" or the "Chelsea apartment house".

The former buildings on the site at West 23rd Street, the old

armory, were destroyed by fire in February, 1878. The Chelsea was under

construction as a cooperative in December, 1882, according to the Record and

Guide (December 30, 1882). But the plans for the cooperative were filled in

January, 1883, for a flat for forty private families.

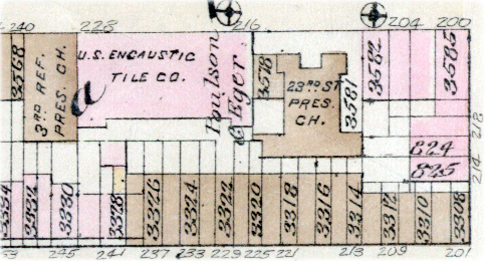

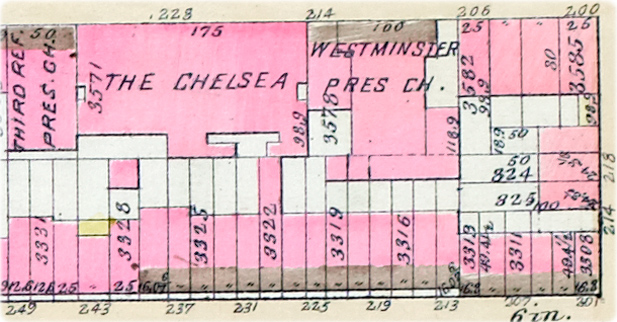

This red-brick building was designed by Phillip G. Hubert (1830–1911), co-founder of the firm Hubert, Pirsson & Co., in a Queen Anne style. The builders were J.B. & J.M. Cornell and Post & McCord. It is eleven stories high in front on the south side of Twenty-third Street and twelve in the rear. It was probably the first 12-story building in the City, but it is just 140 feet high. It was probably the tallest hotel in New York until the construction of the Hotel Netherland in 1893. The Chelsea was constructed at 216-228 W 23rd St., between 1883 and 1885, and opened for initial occupation in 1884 as one of the earliest cooperative apartment houses in New York (Chelsea Association Building).

The erection of cooperative apartment associations were organized under the general corporation act of 1848, under which the various owners became copartners. In 1849, an amendment to the act allowed the formation of stock companies for the purpose of acquiring title to ground and erecting thereon such structures as the stockholders deemed expedient. In an interview to the Record and Guide (October 27, 1883), Phillip Hubert said The Chelsea, then under construction, "will in-fact be a co-operative hotel; that is to say, the co-operators will own apartments of four or more rooms in what will substantially be a hotel. They will be furnished with gas, heat and service, but will pay for their meals like at an ordinary restaurant." Hubert also designed other apartment houses in the 1880s.

Many apartments were purchased soon after the building was under way. In the early 1885, The Chelsea contained nearly 100 suites. About 70 of the suites were in the possession of stockholders, including many firms who were employed in the construction of the building and consented to accept payment of their claims in stock. Of the 30 suites to rent all but a few were taken.

The central section of the front has a high, pyramidal slate roof, flanked on each side by brick chimneys. At each end of the building there are projecting wings. The florid cast iron balconies, a notable feature of the building, were made by the firm J.B. & J.M. Cornell. It has unique iron staircase. The building also had some of the first duplex apartments in New York and one of the first penthouses. It was considered to be fireproof. A portion of the apartments were reserved by the stockholders to be leased for the benefit of the company.

But profits weren't as high as many investors had expected. The Record and Guide (March 6, 1886) reported that «Capitalists who invested so freely in monster apartment houses some years ago have not made the large profits they anticipated. Indeed, some of these enterprises, from a pecuniary point of view, have been disastrous. It is not likely that many more will be built for some years to come, and by that time there will be a "survival of the fittest " among the plans under which they were constructed; that is, it will be found out which apartment house paid best and which did not. It is worthy of note that quite a number of these houses have been changed into hotels. This is true of the Vendome, the "Victoria, the Chelsea, the new house at the corner of Fifty-ninth street and Fifth avenue [probably the Old Plaza].» However, in a second interview given by Hubert to the Record and Guide (February 18, 1888), he said: "Most of the large apartment houses are joint stock companies—that is, home clubs. [...] Some of them have not been successful, but the genuine home club has been so beyond expectation. Let us take the Chelsea, for instance, on 23d street. Not only is every suite rented or sold, but there are continual applications which have to be refused; and if two or three buildings of a similar character were erected they would obtain occupants within a short time." Hubert also said the problem was the change in the law, restricting the height of buildings. In fact, the Real Estate Record Association wrote that "the Chelsea ... a co-operative scheme, that has proven successful." (A History of Real Estate, Building and Architecture in New York City..., 1898).

Years later, however, the Chelsea went bankrupt and tenants were forced to leave the building. It was sold and reopened, in 1905, as Hotel Chelsea, but continued to house some permanent residents. It was then in the heart of the theatre district of NYC. Artists, writers and many celebrities have lived in the Chelsea.

In 1921, the building was sold to the Knott Hotels and A.R. Walty was the resident manager.

In 1926, the Hotel Carteret, an apartment building at number 208, adjoining The Chelsea, was erected on the site of the old Westminster Church. On the other side there is the Chabad of Chelsea, at number 236, founded in 1865. The temple, built in the 1850s, was originally the Third Reformed Presbyterian Church.

In the 1930s, the hotel went bankrupt and it was repossessed by the Bank for Savings. In 1941, Hotel Chelsea was bought by the Chelsea Hotel Corporation, led by Joseph Gross, Julius Krauss, and David Bard. They managed the hotel until the early 1970s. Stanley Bard, David Bard's son, became manager after Gross and Krauss' deaths.

The building was designated a New York City landmark in 1966 and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1977.

In June 2007, the longtime manager Stanley Bard was ousted by the other members of the Chelsea Association's board of directors, led by Dr. Marlene Krauss, the daughter of Julius Krauss, and David Elder, the grandson of Joseph Gross and the son of playwright and screenwriter Lonne Elder III. Stanley Bard was replaced by the management company BD Hotels.

In 2011, Joseph Chetrit bought the property and the hotel was closed for transient guest for renovations. In 2013, the hotel was sold to King & Grove.

In 2015, Hotel Chelsea reopened and the proprietor King & Grove Hotels was rebranded as Chelsea Hotels, but renovation continued as did conflicts with tenants. In 2016, Ira Drukier, owner of BD Hotels, bought The Chelsea.