In the spring of 1890,

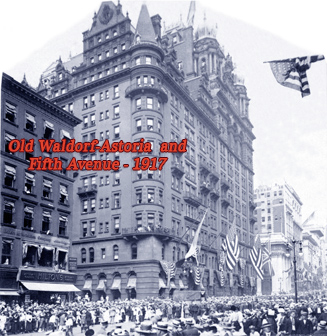

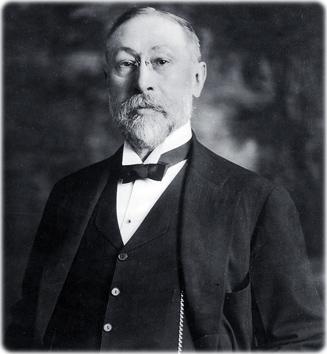

William Waldorf Astor was reported to be about to erect a great hotel upon the site

of his house at the northwest corner of Fifth Avenue and 33rd Street. He discussed this with his estate agent, Abner Bartlett. "I think that we shall

build that hotel", Mr. Bartlett said, adding that George Boldt, in Philadelphia,

was the man to look after it.

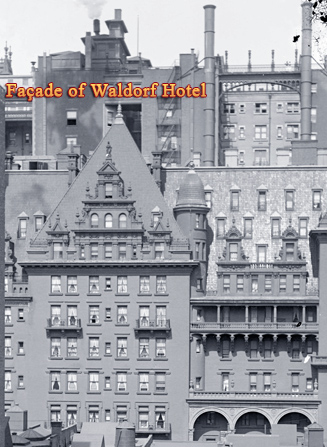

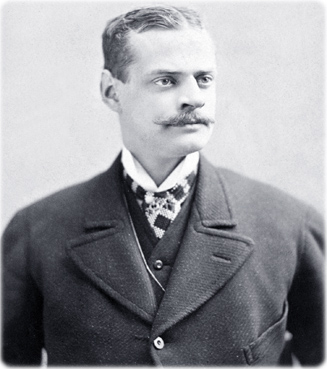

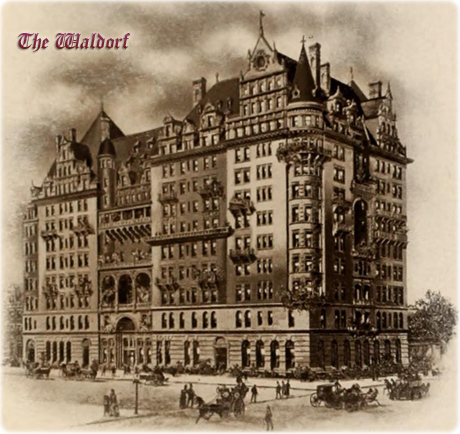

Boldt was the man over the Bellevue, a little hotel in Philadelphia. He was the manner of man, then, who was chosen to make the operation of the new Astor Hotel. It soon was settled that it was to be called the Waldorf, his life work. He accepted after consultation with his wife. Within a few weeks architect Henry J. Hardenbergh, who had designed several notable buildings, including the Dakota Apartments, was engaged upon its preliminary plans and it was not long thereafter before the Astors moved out of their comfortable red-brick house and the wreckers were engaged in its demolition.

Ground was broken on November 1st, 1890. In the late summer of 1891 the gaunt steel framework of the new Waldorf began to show itself over the edge of the tall, tight fence which the contractors had built about the site of the hotel. Boldt, although never relinquishing the full control of the Bellevue, took the house at 13 West 33rd Street (immediately adjoining the Waldorf site), not only as personal living quarters, but also as an office until the new hotel should be finished. Literally he slept on the job, when he slept at all. At no time during the long period of construction was he far from it. When he did go it was either to gain ideas or furnishings for the house.

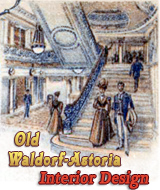

The original intention was to have the Waldorf eleven stories in height. Finally, in deference to a request of Mrs. Boldt, this was increased to thirteen stories. The wife of the proprietor of the new hotel had a sort of superstitious affection for the number thirteen. From the first the idea was to create a super tavern with as little of he typical hotel features in evidence as was humanly possible. There were to be 530 rooms, of which some 150 would be sleeping rooms. There were to be 350 private bathrooms, a feature which alone made a tremendous impression upon the high-grade traveling public of the the time.

In 1892 it was possible to permit the decorators and the furnishings to come into the uncompleted building. The plans for the hotel having been finished, in compliance with his announced plan, the owner William Waldorf Astor returned to England. The few orders or suggestions that he made in connection with the building of the house were chiefly given by cable. As far as is known, he never entered it after its completion but twice, and then but for a few minutes each time. He passed quickly through its corridors and did not lift his eyes from the floor.

Finally, it was a wintry day in February, 1893, when a great banner was affixed to the front of the new Waldorf. In large black letters: Mr. Boldt announces the opening of the Waldorf, Wednesday, March 15, 1893. Temporary offices at 13 West Thirty-third Street.

The actual christening of the original Waldorf took place on the evening of the 14th of March. For months it had been anticipated as a large social function. A huge concert, in aid of St. Mary's Free Hospital for Children and under the direction of Mrs. Richard Irvin, formed the excuse for bringing a most representative group of New Yorkers to the opening of the new hotel. A spring rain was doing its utmost to dampen the party, but failed to keep away more than fifteen hundred men and women that attended the affair. The New York Symphony Orchestra, under the leadership of Walter Damrosch, which had been donated for the evening by Mrs. W.K. Vanderbilt, was the chief feature of the program.

In the same year, the 17-story Hotel Netherland was completed on Fifth Avenue, claiming to be the tallest hotel in the world.

The state apartments of the Waldorf were occupied for the first time on April 15th, just 30 days after the formal opening of the Hotel. A party of distinguished Spaniards, on their way to the World's Columbian Exposition at Chicago, were housed in them. In this group, the precursor of a long line of prominent official visitors to the United States to be entertained under the hospitable roof of the Waldorf, were the Duke and Duchess of Yeragua, the Honorable Christopher Columbus y Aguilera, the Honorable Charles Aguilera, the Honorable Maria del Pilar Columbus y Aguilera, the Marquis Barbolis and his son, the Honorable Pedro Columbus de la Corda. Later came the delightful Princess Eulalie and her suite. On the 19th of April this ducal party held a reception in the hotel which was attended by a hundred of the most prominent women of New York, Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia and Chicago. It was a most elaborate affair. Elaborateness was a peculiar perquisite of the Waldorf. It fairly lived on pomp and ceremony.

New York gazed and gaped at the splendors of its newest tavern. People flocked to the luxurious and glorious Waldorf by the hundreds and by the thousands. They engaged tables in all of its restaurants days and even weeks in advance. They filled its sleeping rooms. Professional guides were engaged, probably for the first time in the history of any hotel. These young men, glib of tongue and pleasing of manner, were hired to direct strangers through the hotel and to spare no details of information in regard to it.

As the spring of 1893 turned into summer, Boldt came to be distinctly worried about the success of his venture. A most temperamental man at all times, he fell into a depressed habit of going to his friends and asking them if he had not made a mistake in going into such a whale of an enterprise. Would he not have done far better if he had remained content with the comfortable earnings of the little Bellevue? Assuredly it had been a mistake opening the house almost at the threshold of oncoming summer. Then, too, the Chicago Fair was not going as well as had been anticipated. The great flow of European visitors that it was to bring into the United States and who could reasonably be counted on for stays in New York, both coming and going, failed completely to materialize. And the shadow of oncoming hard times, the economic Panic of 1893, was already upon the land. No wonder that Boldt worried. And worried long and worried late. On one Sunday of that depressing summer of 1893 there were forty guests in the house, and 970 servants upon the payroll that day. He had excellent cause to worry. Yet Boldt never dismissed a single servant or in any way lowered his standard of service.

The Hotel derived its name from the little town of Waldorf, in the Duchy of Baden, Germany, which was the ancestral home of the Astor family. A picture of the town in stained glass was found over the main entrance of the South Palm Garden, on the Thirty-third Street side of the building (picture above from The Waldorf-Astoria, by George C. Boldt, 1903.).

In the winter of 1893 the Waldorf really began to come into its own. Not only had New York caught on" to the real loveliness of its new toy, but the rest of the country had followed likewise. New York now was coming uptown by leaps and by bounds. Fifth Avenue as a residence thoroughfare, between Twelfth Street and Fiftieth, at least, was gone. In place of the old brown-stone and red-brick fronts were coming shops and offices.

Temporary relief was gained in 1895 when five or six small red-brick residences in Thirty- third Street, just to the west, were torn down and a five-story extension to the main building (so planned in its foundations and construction framework as to be capable of bearing many more floors, if it ever should become necessary) was begun. To make room for this wing, Mr. Boldt sacrificed the original "No. 13," in which he had dwelt prior to the completion of the hotel, and which since then had been occupied by the cigar and wine importation company which he organized under its name. In its place came a new "No. 13," however — a complete private residence built into the hotel structure so that its separate identity could never be suspected, even from the small street door which served as its own individual entrance. This home Mr. Boldt occupied for a number of years — up to the completion of an even larger one in Thirty-seventh Street, just back of Tiffany's.

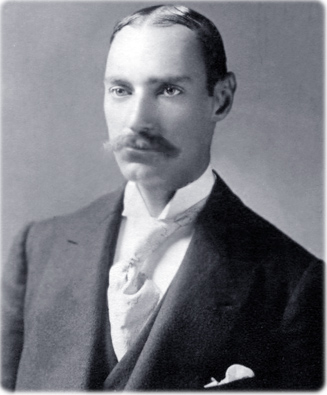

The entire neighborhood was in the course of a rapid transition. The old buildings around about were coming down, right and left. The 34th Street corner was still occupied by the John Jacob Astor residence. There was a long-standing estrangement between the two branches of the Astor family. The John Jacob Astor branch was also represented by an estate agent, Mr. George F. Peabody. The eventual bringing together of the branches was accomplished by Mr. Bartlett, working in consultation with Mr. Peabody. It was then definitely decided to build a hotel on the John Jacob Astor property, to be called the Astoria and to be operated jointly with the Waldorf. Mr. Hardenbergh, who had designed the original house, was asked to prepare the plans for it and it was discovered that the foresight of George C. Boldt had caused the main floor of the Waldorf to be set high enough above the 33rd Street level to come just even with the pavement of 34th Street (there is a considerable variation between the levels of these two parallel cross streets.) You hardly ever could beat the proprietor of the Waldorf on long-distance vision.

John Jacob Astor estate, house of Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, mother of John Jacob Astor IV, while finally agreeing to the joint hotel plan, held tightly to its rights. The Astoria was not only to be built entirely separate from the Waldorf in every way, shape and manner, but Boldt was required to put up a bond that would provide for funds for the immediate closing by brick and stone of every opening in the division wall that separated them. This was done and, in the spring of 1895, the demolition of John Jacob Astor's house was begun. Ground was broken on May 1st, 1895 for the construction of the sixteen-story hotel.

This hotel was named after the town of Astoria, founded in the year 1811 by John Jacob Astor, the first, at the mouth of the Columbia River, Oregon (picture above from The Waldorf-Astoria, by George C. Boldt, 1903.).

By the summer of 1896 the Astoria was well upon its way toward completion. The details of its magnificence were beginning to seep out into New York. There was a tendency on the part of well-to-do folk to make their real homes in the country, coming to New York for but three or four or possibly five or six months in the winter. To cater to these folk was the special desire of the Waldorf-Astoria. Gradually it was to become slightly less a hotel for the mere feeding and housing of travelers and considerably more a semi-public institution designed for furnishing the prosperous residents of the New York metropolitan district with all the luxuries of urban life. With this in view, great attention was given to the planning of the ballrooms and other apartments of public assemblage in the Astoria.

The Astoria side of the combined hotels was formally opened upon the evening of November 1st, 1897. Again there was a great concert, and again it rained — fiercely and furiously. But again the enthusiasm of New York society over its great toy refused to be dampened. Mrs. Richard Irvin repeated her remarkable success of the opening of the Waldorf side of the house. This time the proceeds of the concert were to be given to not less than four institutions: the Loomis Sanitarium for Consumptives, the Babies' and Mothers' Hospital, the Saturday and Sunday Woman's Auxiliary Hospital, and the Babies' Ward and the Day Nursery at the Post-Graduate Hospital. The opening ceremony began in the afternoon with a fairy spectacle, The Realm of the Rose, given by one hundred children of well-known New York families. In the evening was the more formal affair, again a concert — this time by Anton Seidl's orchestra, which was placed in the Astor Gallery. After the concert the guests of the evening went to the great ball- room, where, upon its stage, Mr. John Drew, Miss Maude Adams and their company gave the second act of Rosemary, then a raging New York success. A buffet supper was served afterwards, and again a group of well-known young men acted as ushers to show the entire house to the guests. As a house-warming it was a most complete affair. And as an aid to charity, practically every feature of it being donated, it was a tremendous inspiration.

For the next years the record of the Waldorf-Astoria reads as a succession of successes. Distinguished visitors came to it in greater numbers than ever before.

Mr. Boldt died in 1916. Mrs. Boldt had died some years before. Her passing was a terrible blow to her husband. For the Waldorf- Astoria, the skipper was gone. George Charles Boldt Jr. (1879 – 1958) came, but young Boldt has never had the taste for hotel-keeping that his father possessed. He preferred to seek other pursuits. The Swiss maître Oscar Tschirky (1866–1950) was put on the job, later replaced by Lucius M. Boomer, manager of the Hotel McAlpin, on Broadway.

Because of the success of the McAlpin under Boomer, Thomas Coleman du Pont visualized the reincarnation of the Waldorf. He said: "Boomer, I will take it, if you will run it." Boomer agreed and T.C. du Pont purchased the Hotel, in 1918. Boomer was brought into the overlordship of the Waldorf-Astoria, and then, shortly afterwards, into that of two famous out-of-town houses: the Bellevue-Stratford, of Philadelphia (successor to Boldt's little Bellevue), and the historic Willard's, of Washington.

Boomer was not elected to take direct management of the Waldorf-Astoria. His other business interests would not permit that. Boomer selected Roy Carruthers for the post of managing director of the Hotel. He had had a fine preliminary schooling as managing director, first, of the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, and then of the new Pennsylvania in New York. In 1924, Augustus Nulle took the post.

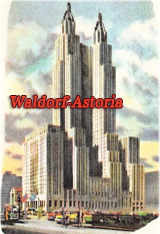

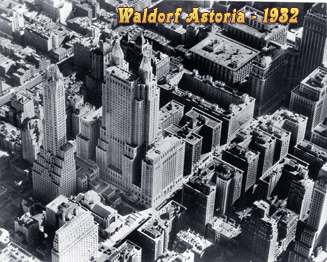

Lucius M. Boomer (1878–1947) was one of the most successful hoteliers of the early twentieth century. He married Jorgine Slettede in 1920. The old Waldorf-Astoria closed its doors on May 3, 1929, and it was demolished in the same year to make room for construction of the Empire State Building. The Boomers retained ownership of the name and, in 1931, a much bigger Waldorf-Astoria Hotel opened on Park Avenue.

Main sources: The Story of the Waldorf-Astoria by Edward Hungerford, published about the second decade of the 20th century, and The Waldorf-Astoria, by George C. Boldt, 1903.